The Slow Death of Focus

- 19 mins

How Digital Overload is Eroding Our Intelligence

For most of human history, intelligence has been seen as something stable—something innate. We assume that our brains today are just as capable as those of previous generations, if not more so, thanks to greater access to education, technology, and information.

But what if we’re wrong?

Am article in this weekend’s Financial Times by John Burn-Murdoch revealed something alarming: over the past decade, our ability to reason, problem-solve, and focus has been declining—and the culprit isn’t biological. It’s digital. You can and should the article in full here

Reading it makes one think that we are in the midst of a cognitive crisis, one that few are talking about. It’s not just about IQ scores or school performance. It’s about our ability to think deeply, engage meaningfully, and resist the lure of distraction.

The Evidence of Decline

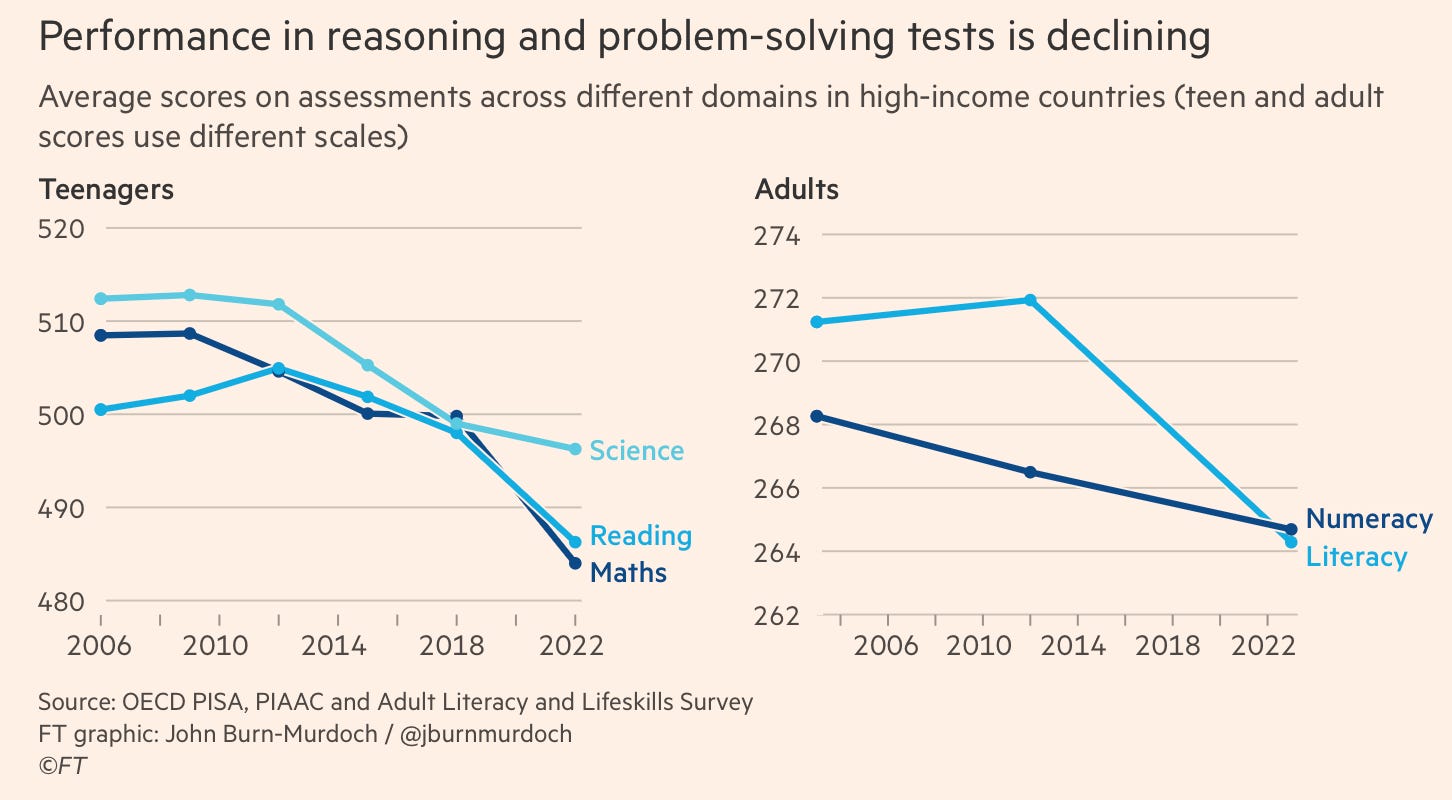

The clearest sign of this shift can be found in global education and skills assessments. The OECD’s PISA tests, which track 15-year-old students’ reading, maths, and science performance worldwide, show that scores peaked in 2012—and have been falling ever since. Depressingly, similar traits can be seen with adults, as the below charts present from John’s FT article, pointing to a significant drop in problem-solving and reasoning ability across all age groups.

One particularly shocking statistic: in high-income countries, 1 in 4 adults can no longer “use mathematical reasoning when evaluating the validity of statements.” In the US, that number is 1 in 3.

As a keen follow of cognitive scientists like Steven Pinker who have long been advocates of both rationality and reason as the principle driver behind human flourishing, I find this trend particularly disturbing as, for me, it goes to the heart of our contemporary political and cultural discourse. Do we still have the cognitive faculties to discern truth from facts? Because in answering that question with a resounding “yes” will see the (hopeful) end of populism and the demagoguery it supports. If we’re slowly but inexorably moving towards a conclusion of “no”, I do fear for what it might spell for the political future, and for Enlightenment values more broadly.

The Digital Hypothesis

Interestingly, this decline didn’t start with COVID, although that certainly exacerbated matters for the young who were excluded from schooling and from the disciplines that formalised education imposes upon them at a rather crucial stage in their development. In fact, the largest drops happened between 2012 and 2018, long before the pandemic disrupted education but just at the time that smartphone adoption and digital technologies (in particular social media) propagated throughout the young.

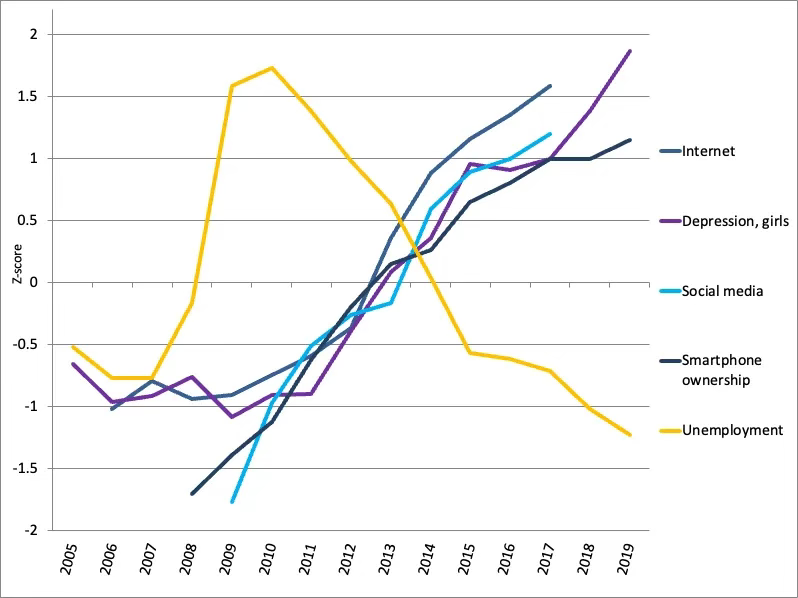

The below graph is taken from Prof Jean M. Twenge’s most excellent blog, Generation Tech, in a piece entitled “Here are 13 other explanations for the adolescent mental health crisis. None of them work”. If you’re not familiar with Jean’s work, she is one of the leading proponents of the psychological community’s clarion call to parents to stop providing their children with unfettered access to smartphones and social media, speaking, rightly, to their declining mental health as a corollary to the declining cognitive aptitude outlined above. She works regularly with Jonathan Haidt and I’d strongly recommend anyone interested in taking a look at both of their blogs (Jonathan’s After Babel is a must)

The purple line points to depression in girls, the light blue is the adoption of social media, and the dark grey, proliferation of internet and smartphone ownership. It is in the same period - the 2012 bracket - in which we see a rapid upsurge in both mental health issues, and in the decline in our academic potential. Something to consider.

And whilst many social scientists - Steven Pinker and Pete Etchells to name but two who I greatly admire - will point to how correlation is not the same thing as causation (basically suggesting that there may be many other reasons to suggest this trend…) I can’t help but intuitively conclude, as a parent and erstwhile phone addict, that it is down to our problematic relationships with these infernal machines in our pockets.

I am going to put down what I believe to be true, with the heavy caveat that it is based on anecdote, inference and feeling, not empirical facts. I have no meta-analysis to back these assumptions up, just a keen sense, based on my own behaviours (that I’m trying to control) and how I feel (but don’t know) that children, not primed with the self-control I tell myself I have (or lack thereof), would fall more prey to the sinister machinations of my machine.

How our digital consumption has changed

I like to frame this as a comparison between how you and I might have used the internet, say, twenty years ago. If we went back any further, for many of us it would just conjure up nightmarish sounds of the dial-up connections that AOL provided us with, and endless hours of whirling blobs on our heavily pixelated screens, waiting for something to pop back as a result to our queries. But 20 years ago, I think it’s safe(ish) to say that most of us were using it to search. Some of us (un)lucky types might have been introduced to Facebook in University (when you could “poke” people you fancied from the library but never had the heart to go and chat to in person), but for the most part, the internet was transactional and based on utility of information transfer. You had a question, you looked it up, you read an article, you learned something. There was a beginning, a middle, and an end and in that, the internet was a tool to achieve an end point, after which we returned to apply that result to our work / life or, as in my case, abortive attempts at study (curse you and your pokes Mark Zuckerberg).

The internet was quick(ish) or at least relative to what we’d experienced but principally for me, it was contained - you had to get to your laptop, or pull it out to linkup to then search. And because of that action and energy, you had a focus and intent for its use. A reason, and an end.

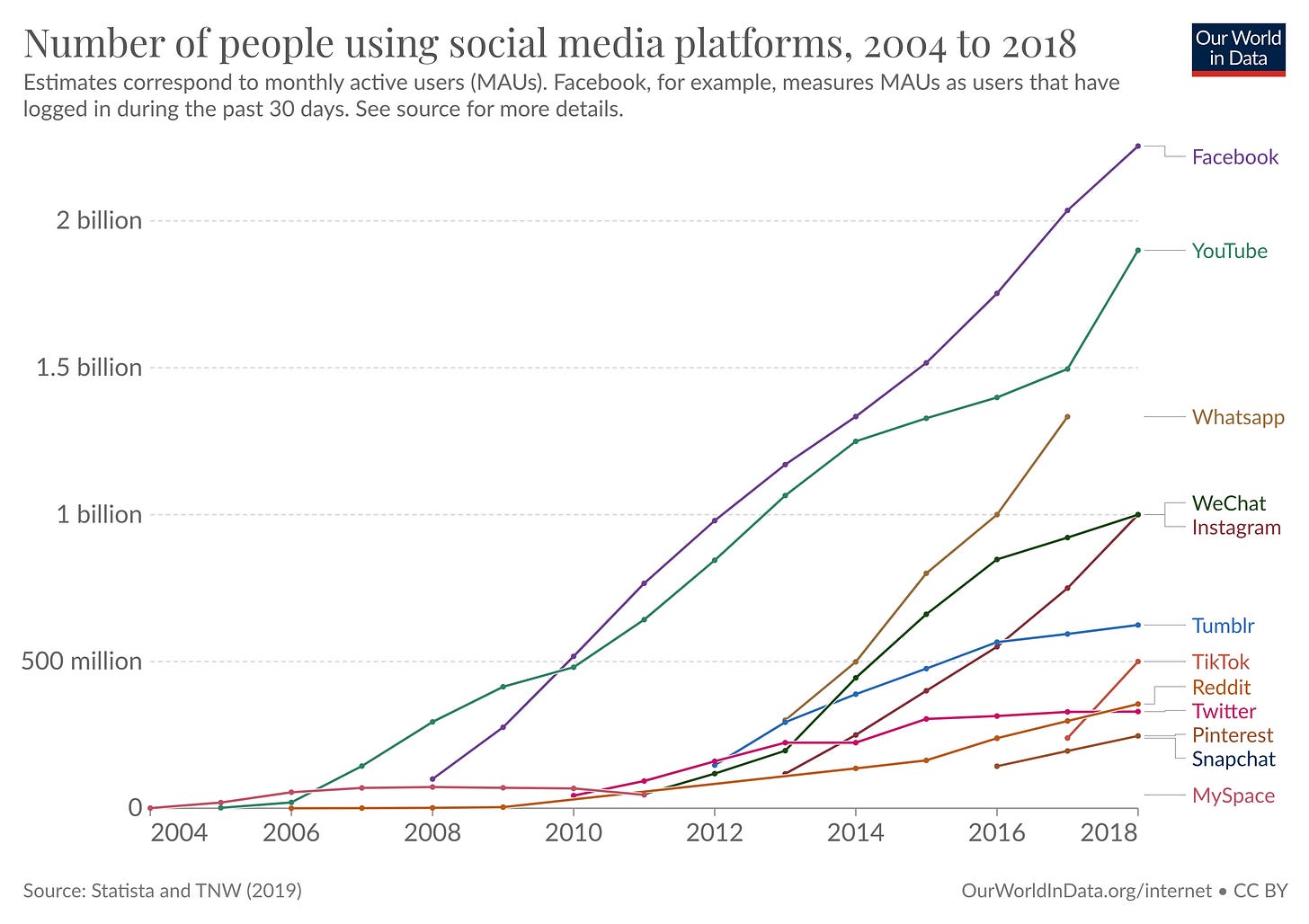

What’s changed? Well clearly now things are exponentially faster and you can now access whatever you want, whenever you want, direct from the phone in your pocket (iPhones were not, I think, released until after my sad and sorry days in University, where we no doubt suffered miserably socially disconnected existences without that instantaneous digital connection available to us all of the time. ). And, social media changed the landscape from information transfer, to social connection, and then entertainment (read news and any form of content). The below chart from the World in Data is a bit out of date now, but should evidence the explosion in social media adoption over the period in question

Roughly at the same time (and probably in response to these developments) news moved from being a once a day affair, where we’d get a lovely recap of the day’s principal events with Trevor McDonald, to a 24 hour news cycle where everything had to be reported at all times and in real time.

The unstoppable rise of content for content’s sake - the sheer volume and ubiquity of production - has led the media (and countless influencers) to really hone in one that most unique of human psychological frailties: the negativity bias. If you don’t really know what this is, you should see Daniel Kahneman & Amos Tversky’s 2013 work that proved we care about and remember always the things that are most sensationally nasty and negative in this world…so if you want to be remembered, do something awful and people will start talking about you and if you want to capture people’s attention (news / media) then you need to fan the flames of sensationalism to get seen, particularly when there is gigabit upon gigabit of crap being thrown out there every second of every day!

So, going back to our “good old days” or transactional searching for a solution for a specific problem, what do we do now?

Declining Reading Habits

Well for many of us, we scroll (“Doom scrolling” as its known, wherein you can lose hours of your life and most of your soul to just being sucked into the algorithm that (primarily) social media companies leverage to vampirically suck you dry until you have no sense of time, self or purpose in life… and you close your eyes at 4am, finally having put your phone away or having just fallen asleep with your phone across your face…I digress. But you get the point - we’re bombarded with so much pointless claptrap that we not only waste what limited time we have but develop the anxiety of missing out for when those manipulative nudges disappear…

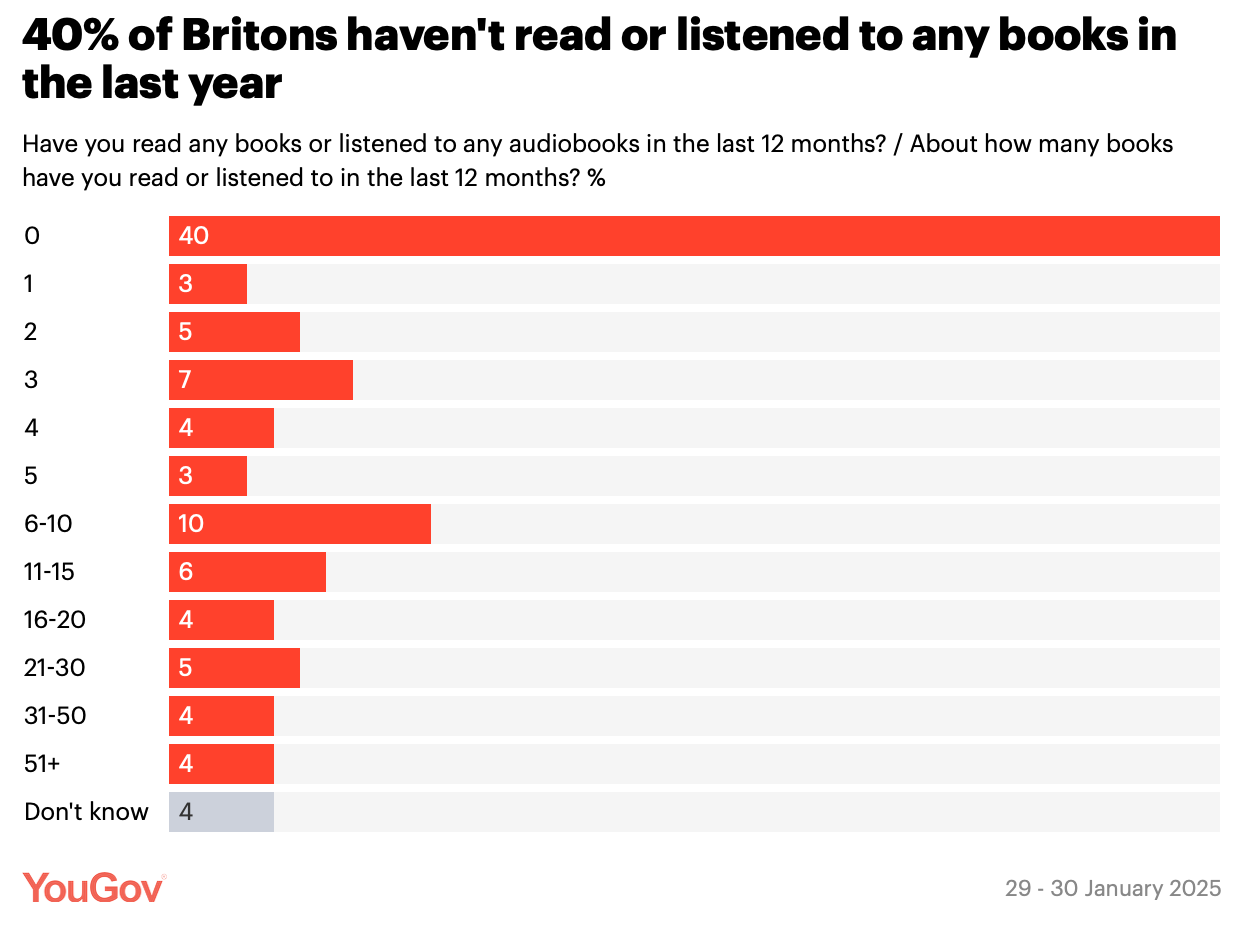

So instead of searching with intent, we drift and scroll. Instead of deep reading, with full focus, we skim (if we’re even reading at all - see the rather depressing findings from YouGov’s recent poll on adult reading habits from March 2025, and the National Literacy Trust’s report that children are, for the first time, listening to books more than they are actually reading them)

I don’t want to present myself as a luddite who wants to smash up the phones. My son Tali has a Yoto (which ostensibly allows for audio books even though we only really use it for the relaxing music it plays to finally get him to go to sleep) but I think that there is something to be said about the cognitive upside of doing something that’s just a little bit harder than passively absorbing information. The effort begets retention, perhaps. Or as Seneca said:

“Difficulties strengthen the mind, as labor does the body.”

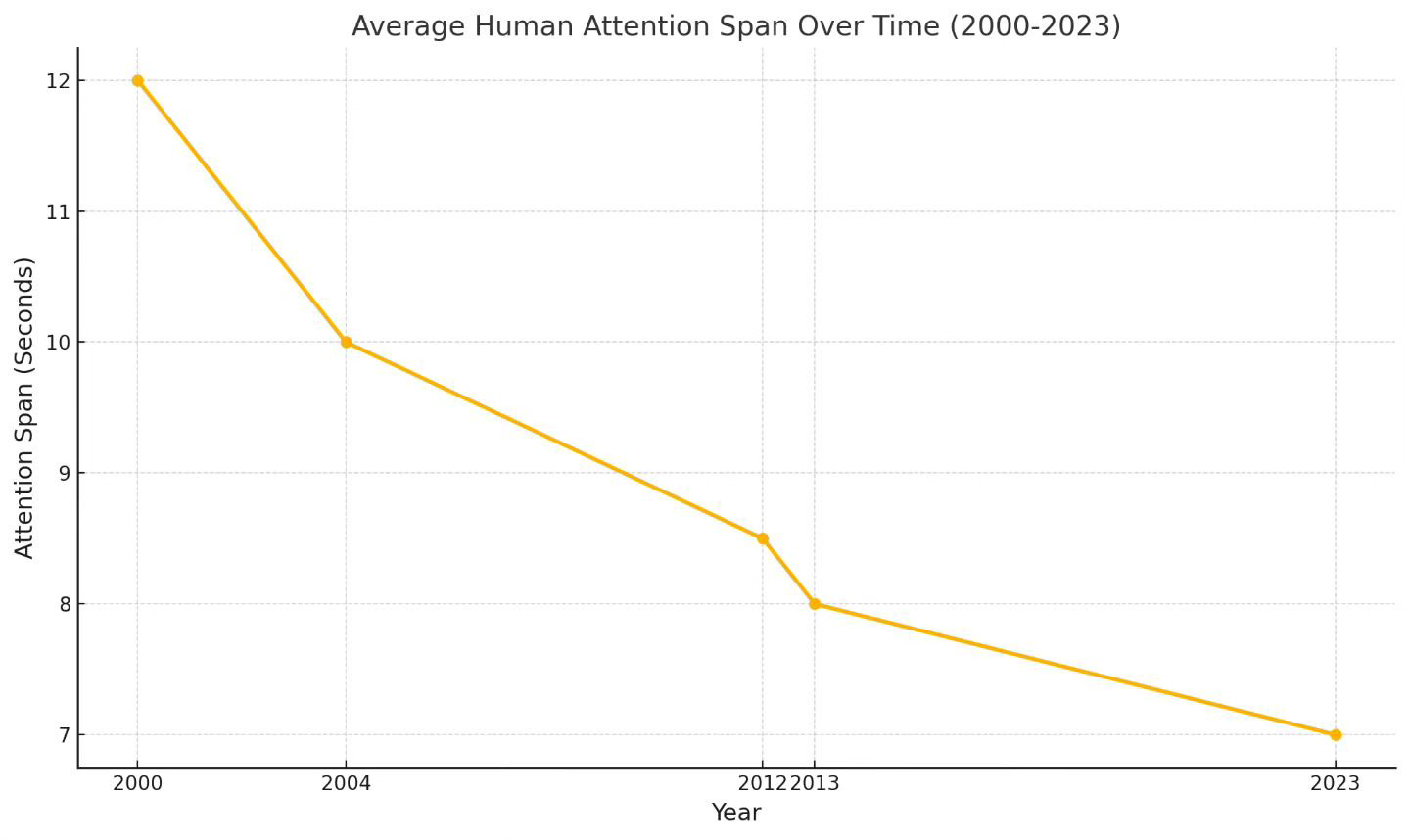

And yet the same doesn’t appear to be true for the digital multi-tasking we tend to do with all of these notifications going off left, right and centre. Engaging in digital multitasking elevates cognitive load, leading to mental fatigue, diminished concentration, and impaired decision-making. This heightened cognitive demand hampers our capacity to process information effectively, according to research by Prof Kamrul Hasan. Social media, infinite scrolling, and real-time notifications have fundamentally rewired how we engage with information - we are constantly switching between distractions, never lingering long enough to process or internalise ideas.

Now I will get shouted at for the above because, yes, how one defines “attention span”, who you use in your sample set and, indeed, how you measure as nebulous a concept as attention is going to make this a problematic chart to say the least. Most of you would have heard the charge that we’re now teetering on the edge of having the same concentration span as a goldfish (we’re now at 7 seconds, and a goldfish apparently can master a whole 8…even though I’m unsure how they measure a goldfish’s attention…there isn’t that much for them to observe or remain focussed on in their bowls…could they just be bored?). But whatever way you look at it, just as I do with the rise in mental health problems in our young people that suspiciously correlates to the massive upswing in both digital proliferation and social media adoption, you can infer that the trajectory isn’t what it should be even if you are to dispute the causation.

Some ideas for solutions

1. Reintroduce Real Reading

Make books—physical books—a non-negotiable part of your life and your child’s life. Reading isn’t just about knowledge; it’s about training the brain to focus, sustain attention, and engage deeply.

2. Set Screen Boundaries

Not all screen time is bad, but passive, endless scrolling is. Set limits, especially for kids. Encourage screen-free zones, no-phone times, and intentional, mindful use of technology.

3. Let Boredom In

Boredom isn’t a problem—it’s the birthplace of creativity and problem-solving. Don’t immediately turn to screens to fill every moment. Let your mind wander. Encourage kids to sit with their thoughts.

4. Make Digital Consumption Active, Not Passive

Instead of endlessly scrolling social media, choose intentional engagement—listen to a podcast that makes you think, read long-form articles, write instead of just consuming.

Die Inhalt ... ist das Opium des Volkes

I’m borrowing a phrase from Karl Marx here and bastardising it somewhat. His original quote was of course:

"Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people."

in which he pointed to the seductive comfort of religion, which served to both distract and give succour to the oppressed, providing illusory happiness in an unjust world while preventing them from challenging their socio-economic conditions. In my header, I’ve changed “Religion” to “Inhalt”, which is Content.

Content, I fear, is the new religion - it stupefies us, and, in much the same way, creates a new absolutism that we can see so clearly and violently articulated with every tribal inflection between the various identity groups that have become our sad and sorry culture. It very much fans the flames of our own discontent, and yet here we are, seemingly unwilling or unable to pull ourselves out of the mire, as we surely must before it is too late. We must surely return to being able to discern truth from facts. Because it was Hannah Arendt, who warned us of what would come next…

"The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction… no longer exists."

Focus can be rebuilt. Intelligence isn’t disappearing—it’s just being underutilized. But we have to make active choices to reclaim it.

The first step? Put down the phone. Pick up a book. And teach the next generation to do the same.

It’s time to fight for focus.

.webp?width=200&height=114&name=Hatching%20Dragons-Logo-v2-01-2-1%20(1).webp)